Small buttons and socks

- Details

- Category: Testimonies

Adolphine De Gezelle, together with her mother and her brother Albert, fled to England in 1914. She was seven and her brother was nine. Her mother, Louise-Marie Hermans, worked as a housemaid for the Ghent public prosecutor. When he fled to England, she went with him.

Upon their arrival in England, both families got separated. Adolphine had only dim recollections of the journey, but she could talk about life in England endlessly. They lived in Taunton (Somerset) for four years. She had vivid memories of this hill town, and of the church, the castle and the school. The latter was situated next to the vicar’s house, where she was allowed to play the piano during playtime and often had to swallow a spoonful of cod liver oil, given to her by the vicar’s maid. The latter, to take away the nasty taste of the oil, always operated as follows: first, she poured some orange juice in a wine glass, she then added a spoonful of cod liver oil – which floated on the surface of the juice – and finished it off with more juice (without mixing the ingredients together). Adolphine had to take a deep draught in order not to taste the oil. Porridge with golden syrup was served for breakfast. The English well-to-do were very fond of Belgian dishes. Adolphine’s mother demonstrated her cooking skills in the manor houses in the neighbourhood.

The family was living in a small house just outside town. Adolphine’s mother was not entitled to an allowance, but she did receive coupons to buy all kinds of things. And she did some odd jobs to make a living. For example, she was sewing buttons on blouses. They never failed to attend mass on Sunday, as they were taken there in a coach. The local population did not really suffer from the war, but they felt pity for the soldiers at the front. They knitted woollen shawls and socks for them. Adolphine did so too, on her way to and from school. She was even awarded a medal for it: ‘knitted the largest number of socks’.

On Christmas Eve the family used to be invited by the Irish dean O’Chaunessy. The three of them then slept in the bishop’s guestroom. The children hung their stockings on the door knob and found them filled with sweets the next morning. They were also invited to the parish Christmas celebration. A huge Christmas tree, reaching almost to the ceiling, had been put up, and lots of gifts were lying under it (they were not packed up). Among them was the doll she had always longed for, with blond curly hair, a cute little face and a rosy dress.

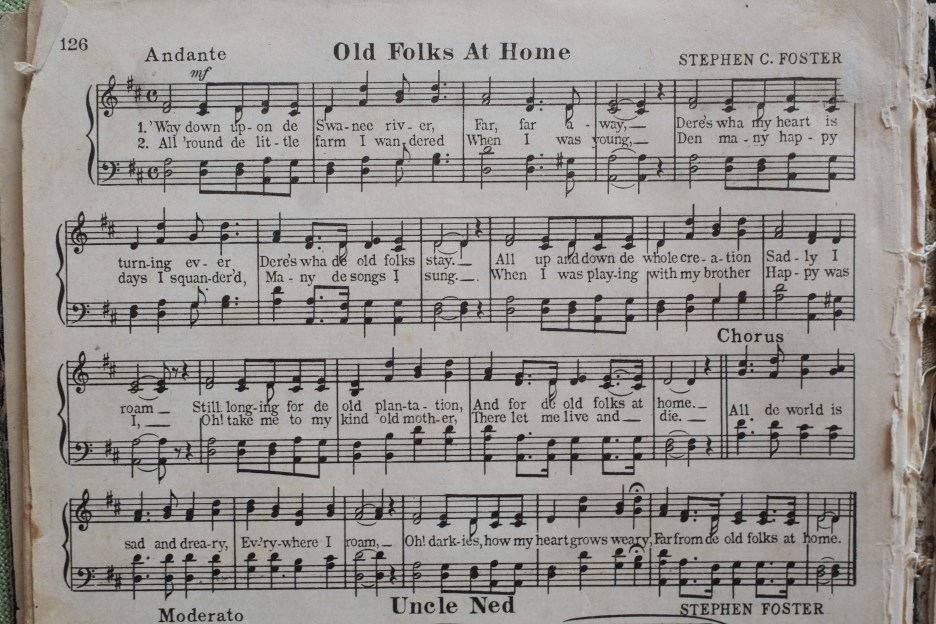

Adolphine was absolutely delighted to hear that the doll was hers. However, her mother found her a bit too young to play with such a precious doll and put it in a suitcase in the attic. Nevertheless, when her mother went shopping, Adolphine sneaked up the stairs and cuddled her doll for a few moments. Adolphine never stopped to enhance her knowledge of English. She continued to read a lot in English and returned to Taunton in the 1960s, together with her husband. They visited the house where she had lived, and the school and the vicar’s house as well. Essentially, nothing had changed. A portrait of dean O’Chaunessy hung in the vicar’s house. When Adolphine saw it, she was so overcome with emotion that she started to cry. Unfortunately, a fire broke out in Adolphine’s home in the summer of 1931. All her most treasured English possessions were burnt. Only a piano booklet of English popular songs still testifies of her stay in England.

Sources:

Testimony by Gabriëlle Van Daele, who heard the story from her mother and grandmother

Thanks are due to Lieve Tirelire from the heemkundige kring Gitschotelbuurschap-Borgerhout and Jolien De Vuyst (Department of Social Work and Social Pedagogy at Ghent University), interview on Storytelling Day at the Red Star Line Museum (Antwerp)